Super Macro Underwater Photography - The Definitive Guide, Part 1

Part 1 – The Basics

by Keri Wilk

Introduction

Being a part of designing and manufacturing underwater super macro optics for ReefNet, I’m frequently barraged with questions about super macro tools, and optics in general. Feeling like a broken record over the past few years, I’ve decided to compile a brief guide to the ins and outs of super macro photography. Along the way, I’ll do my best to explain some optical phenomena that are often misunderstood.

While this article pertains mainly to SLR/DSLR photography, most of the concepts and techniques are relevant and accurate for other recording media (video, point-and-shoot, medium format, etc.). During the majority of the 15 years that I’ve been shooting underwater photography, I have used Nikon camera bodies (preceded only by Nikonos III and Nikonos V), so I ask that you bear with my skew and omission of references to specific Canon, Olympus, and other brands and their associated gear. The information is relevant for all brands.

While this article pertains mainly to SLR/DSLR photography, most of the concepts and techniques are relevant and accurate for other recording media (video, point-and-shoot, medium format, etc.). During the majority of the 15 years that I’ve been shooting underwater photography, I have used Nikon camera bodies (preceded only by Nikonos III and Nikonos V), so I ask that you bear with my skew and omission of references to specific Canon, Olympus, and other brands and their associated gear. The information is relevant for all brands.

Now, you should be warned…I don’t (and will not) claim to be the foremost expert on any of the topics that I’ll be discussing. However, over the years I feel that I’ve gathered enough knowledge through studying optics, and good old trial-and-error, to make this guide useful to anyone looking to learn or refine an approach to super macro underwater photography.

Definitions

Before discussing the various aspects of super macro photography, it’s important to distinguish it from other genres of photography. The fundamental concept of image magnification is also briefly discussed here, as it will be vital to an understanding of the majority of this guide. Each of the following definitions has been synopsized from various reputable scientific photography resources cited at the bottom of the page.

Image Magnification

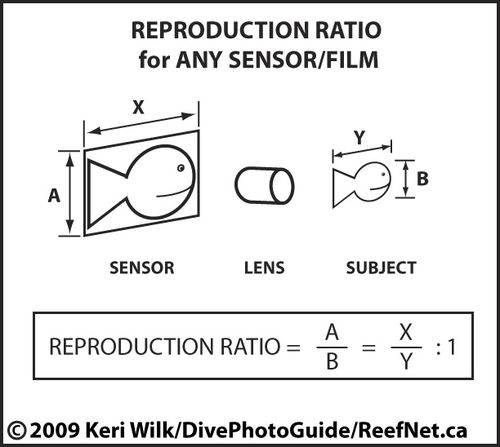

In photography, this refers to “transverse magnification”, which is determined by dividing the image height (on your film/sensor) by the object height, i.e. the height of the subject being photographed (width can also be used):

10.5mm of a ruler filling the frame of my Nikon D300 (sensor is 23.6mm x 15.8mm),

resulting in approximately 2.25X magnification. Image was taken with a Nikon

105mm lens plus a ReefNet SubSee Magnifier @ 1/320s, f/11, ISO 200.

Magnification is alternatively expressed as the reproduction ratio:

For example, when using a camera with a ‘full frame’ sensor (36mm width x 24mm height), filling the frame with a 12mm tall subject corresponds to 2X magnification (2:1 reproduction ratio), since:

-OR-

reproduction ratio = 24mm:12mm = 2∶1

Similarly, filling the same frame with an 8mm tall subject would correspond to 3X magnification (3:1 reproduction ratio), and so on. The same applies to sensors/film of any size, as shown in the diagram below:

People are often tempted to add a “sensor crop factor” to the magnification of a given setup, but this should be avoided when true magnification values are desired, since the sensor size has nothing to do with what is happening optically. Instead, when including this “sensor crop factor”, magnification values should be interpreted as apparent magnification only. I’ll go over this in more detail in the Optical Misconceptions section.

Macro Photography

This term’s definition is highly variable from source to source. An old school photography book that I have defines it as producing images ranging in magnification from around 1:100 (1/100th of life-size) to 1:1. While this may seem counterintuitive, etymology can help us understand the reason for such a definition. “Macro” comes from the Greek word makros meaning “large”, so it follows that “macro photography” can be interpreted as “photography of large subjects”.

But when is the last time someone showed you a picture of a shark and said “Check out this great macro shot I took!”? Probably never, because over time this broad definition has been greatly narrowed. Now “macro photography” generally refers to taking pictures of very small subjects, usually in the reproduction ratio range of around 1:6 to 1:1. The extreme end of this range, i.e. 1:1, is commonly referred to as “true macro”.

Close-up Photography

Although no universal theoretical definition for close-up photography exists, it can once again be classified by specifying an approximate range of reproduction ratios that it encompasses. Most scientific photography resources consider reproduction ratios between 1:10 (or 1:20) and 1:1 to be close-ups, regardless of the camera lens used. However, some sources classify this type of photography solely by proximity to the subject (i.e. anything photographed within 1m/3ft is literally a close-up), rather than by reproduction ratio. By this definition, you could be shooting “close-ups” with your close focusing fisheye lens! Of course, "close-up" is most commonly understood in the spirit of magnification ratio.

If you compare the reproduction ratio range that is now commonly associated with macro photography, you’ll see that close-up photography is essentially the same thing. For this reason, I’ll be using the words “close-up” and “macro” synonymously throughout this article series.

Photomicrography

This refers to using compound microscopes (objective lens + eyepiece lens) to produce images in the reproduction ratio range of approximately 30:1 to 2000:1. This has almost no relevance to underwater photography, so there’s no need to discuss this further. But it's pretty cool!

Photomacrography

You may think this is the same as “macro photography” defined above, but that is not the case. By definition, “photomacrography” is defined by a reproduction ratio range from 1:1 to around 30:1 (this is the practical limit). To a degree, iphotomacrography is defined by the equipment that was used to create this magnification. Photomacrography equipment is generally more elaborate and professional-grade than equipment used for close-up work.

When “standard” lenses are coupled with extension tubes, teleconverters, or other optical tools underwater, useable images of up to around 10:1 can be achieved. Beyond that level (10:1 to 30:1), the use of specially designed photomacrography lenses would be more appropriate for maintaining image quality. This type of equipment is incredibly difficult to use underwater, as most photomacrography is acheived where the subject, and equipment are all physically supported and controlled (ie: a microscope or in a studio).

Super Macro Photography

Most photographers would agree that super macro photography means the production of photos with reproduction ratios greater than 1:1, so it makes sense that super macro is just a subset of (or even a synonym for) photomacrography. Generally, in order to achieve these levels of magnification one needs to use a ‘normal’ close-up lens with one or more additional specialized tools.

OK, so now you know what super macro photography is, but you might be wondering how this type of photography is possible, since most popular macro lenses don’t offer more than 1:1 magnification. I’ll briefly discuss the main tools used to accomplish supermacro, in Part 2.

Resources:

Richard A. Morton, “Photography for the Scientist”, 1984

Charles E. Engel, “Photography for the Scientist”, 1968

Rudolf Kingslake, “Lenses in Photography”, 1951

Rudolf Kingslake, “A History of the Photographic Lens”, 1989

Leonard Gaunt, “The Photoguide to the 35mm Single Lens Reflex”, 1973

Francis A. Jenkins and Harvey E. White, “Fundamentals of Optics”, 1957

RELATED CONTENT

Featured Photographer

Antarctica

Antarctica