Photographing Fish Spawning Aggregations

A spawning aggregation is one of nature’s most fascinating spectacles. Thousands or tens of thousands, or even millions, of fish gathering for the purpose of spawning is a sight that comparatively few divers ever get to witness. For the small number of lucky underwater photographers who have the opportunity to shoot these exciting events, there are various photographic challenges that must be overcome if one is to take home compelling images.

This article is meant as a starter guide to capturing spawning aggregations in Palau, one of the most interesting locations where it’s possible to witness a variety of species spawning on a regular basis. Many of the techniques discussed here can be applied to other locations where these amazing phenomena take place.

Where to Find Spawning Aggregations

Fish aggregate for a variety of reasons: for safety, for migration, even for feeding. Perhaps one of the most impressive of these aggregations is when thousands (or millions) of a single species come together to mate and spawn. There are two types of spawning aggregations: resident and transient. While transient aggregations occur with larger species for short durations and are uncommon, resident aggregations can be observed on a regular basis (based off lunar cycles) at predetermined locations.

Since it’s a necessity to reproduce, spawning aggregations can be found across our blue planet. Having said that, there are several notable destinations known to produce reliable spawning aggregations for specific species, such as goliath groupers in Jupiter, Florida. In Palau, we are able to witness a variety of species spawning on a regular basis, including red snapper and bumphead parrotfish.

Photographing the Aggregations

All aggregations are unique in terms of location, moon phase, courtship, and size. But all have the same results: Lots of fish arrive, reproduce and leave. Getting good shots involves patience, knowledge of their behavior, and a lot of luck and determination.

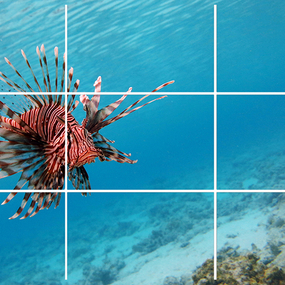

Ambient light is most likely to be your tool in the beginning. Some species are extremely shy before spawning, like bumphead parrotfish. Getting close enough to light them up with a strobe is practically impossible without disturbing them and affecting the spawning. A fisheye or wide-angle lens with the right timing will be a good formula for great schooling shots.

Most schools will aggregate close to the surface before spawning for a short period of time, allowing great opportunities to shoot up and make the most of the low-light conditions. Be careful, however, not to overexpose the surface area. It’s always easier to bump up the levels in the lower half in post-production later.

Once you have succeeded in getting some good results with ambient light, then you can try using strobes. Getting close is the key to success—as strobes will not reach more than five feet, and the further away you are the more backscatter will be lit up. Using strobes will only be possible with some species that are more accepting to you or your approach, such as the twin spot snapper (Lutjanus bohar) or blue lined sea bream (Symphorichthys spilurus). Strobe placement is vital for getting a good balance of light throughout the school.

The Mating Dance

Sexual dimorphism can be seen in the form of a change in a fish right before spawning. Some fish will show bars, some will show banding, while others will completely change the color of their heads. Depending on the species, a kind of dance will unfold—rubbing, chasing, moving in time back and fourth—before the main event begins. These moments tell the story, and although capturing them is challenging, they show how interactive each species can be with one another.

The Spawning Shot

The money shot, as it’s called, involves fast-moving fish, with the foreplay or mating dance energizing the whole school. Obviously, with fast-moving subjects, you’ll need fast shutter speeds to make sure you freeze the action. Start with a shutter speed of at least 1/160s, which will allow you to balance your ISO level and aperture accordingly. Weather, as well as time of entry, will both make a difference. The amount of sunlight changes very quickly during dusk and dawn, and a matter of 30 minutes during your dive will make an extreme difference in terms of what exposure settings are most appropriate.

Choosing the highest possible ISO depends a great deal on your camera’s and lens’ capabilities, but I personally rarely go above an ISO of 800, as it will start looking grainy in low light beyond that. If light conditions are favorable, I like to tighten my aperture to gain extra depth of field, so that more of the school is sharp front to back. Balancing all of these settings at the same time at six o’clock in the morning can be a little daunting and having a ballpark idea before you jump in is very helpful.

Getting close without disturbing their behavior is key to getting great shots. Learning the pre-spawning behavior and knowing what signs to look for before the fish spawn will allow you to be in the right place at the right time, giving you an opportunity to get the shot that no-one else has. This is a question of spending more time in the water and seeking advice from your divemaster.

Using a wide-angle lens will give you a more dramatic shot. Mostly, if possible, I will shoot with a 15mm or 16mm fisheye, trying to catch that shot of close-up foreground spawning with hectic spawning in the background. However, after many years and many attempts, I’ve learned that some species of fish will just not cooperate, and using a 16–35mm or even a 50mm on a full-frame camera is the safe option, as it fills the frame with the subject without scaring it away.

Photographing Predation in Spawning Aggregations

During most of these aggregations, I have seen bull sharks and blacktip sharks hunting the school. On multiple occasions, I have witnessed, from less than 10 feet away, a shark strike and tear apart a tired and weary fish after spawning—just missing that lifetime shot. Such experiences have taught me that during these dives, one must always be aware that something epic could happen at any time. Quick reactions and awareness could get you that shot.

Sharks aren’t the only predators commonly seen during such aggregations; intra-species predation on the newly born fish also occurs. Black snappers (Macolor niger) feeding on the cloudy gametes makes for great photo opportunities, and they are so intent on feeding you can usually approach without them fleeing. It’s a real treat to be able to capture these hungry predators getting their early breakfast, mouths wide open, feeding on the fast-disappearing young.

Final Thoughts

There are endless photo opportunities when shooting spawning aggregations. Each school has its own unique style and pattern. Learning their behavior and understanding how to look for telltale signs of a spawning rush about to happen will get you what you’re looking for. Remember that what works well with some fish won’t work well with others.

Diving during these events in Palau on a regular basis, I have been very fortunate to be able to improve my chances of getting great shots over time. If you are lucky enough to get the opportunity to shoot a spawning aggregation, make sure you take the time to prepare and plan carefully, bring capable equipment that can perform well in difficult low-light conditions, and, once you’re in the water—as the drama is unfolding—always be ready for something unexpected to happen.

RELATED CONTENT

Featured Photographer

Antarctica

Antarctica